When Digital Art Was Avant-garde

In 1960, a Brazilian artist named Almir Mavignier stopped in Zagreb on his way from the Venice Biennale to a vacation in Egypt. There, he met people in the Yugoslav scene who, in his words, asked him “what hitherto unknown artistic movement had made its presence felt at this Biennale.” Mavignier’s reply was simple: “None,” he said.

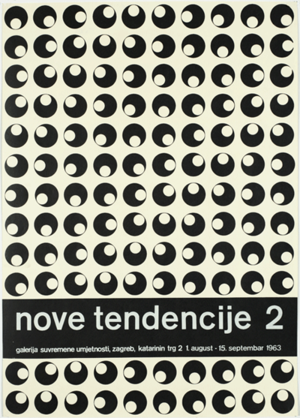

Matko Meštrović, a Zagreb art critic, had also been to the Biennale that year and shared the Brazilian’s disapproval of the international art market. The two began to develop the idea of an exhibition that would come to be called nove tendencije [New Tendencies]. Curated by Mavignier, the art shown would be the result of his experiences of “go[ing] to artists’ studios and gett[ing] acquainted with artists who are experimenting with new ideas and new materials.”1 Only there, not at art fairs or industry shows, could new artistic directions be discovered.

Most of the artists selected for that first show were deeply influenced by the materials, techniques, and theory behind Constructivism. By 1960, the Stalinist repression of the revolutionary art movement (in favor of Socialist Realism) was already decades past, but many artists were still attracted to the ideas of creating art that was for the masses and in service of freeing workers from exploitation. In an exhibition catalogue, Meštrović wrote that art “has a markedly constructive sense especially when… art seeks ways to extend its energies into immediate social action.”2 None of those involved, I don’t believe, had any illusions about how difficult a task this would be. For that reason, the group’s touchstone became ‘Art as Research.’

To say that Nove tendencije was a success would be an understatement: it excited the entire art world. People did in fact wonder whether they were witnessing something truly new in art. As the next editions of New Tendencies were being put together and shown in Zagreb, the art began to travel internationally, being shown at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, the Museum of Modern Art, and, funnily enough, at the 32nd Venice Biennale in 1964.

This exposure led the more commercial sides of the art world to take an interest in the emerging style. Especially after the exhibition in New York, the artistic trends on display at the New Tendencies shows even began appearing on dresses and wallpapers. Although in principle consistent with Constructivist practice, the manufacture and sale of these consumer goods caused “the artists to wonder if research had simply ended up in the production of works of art.”3

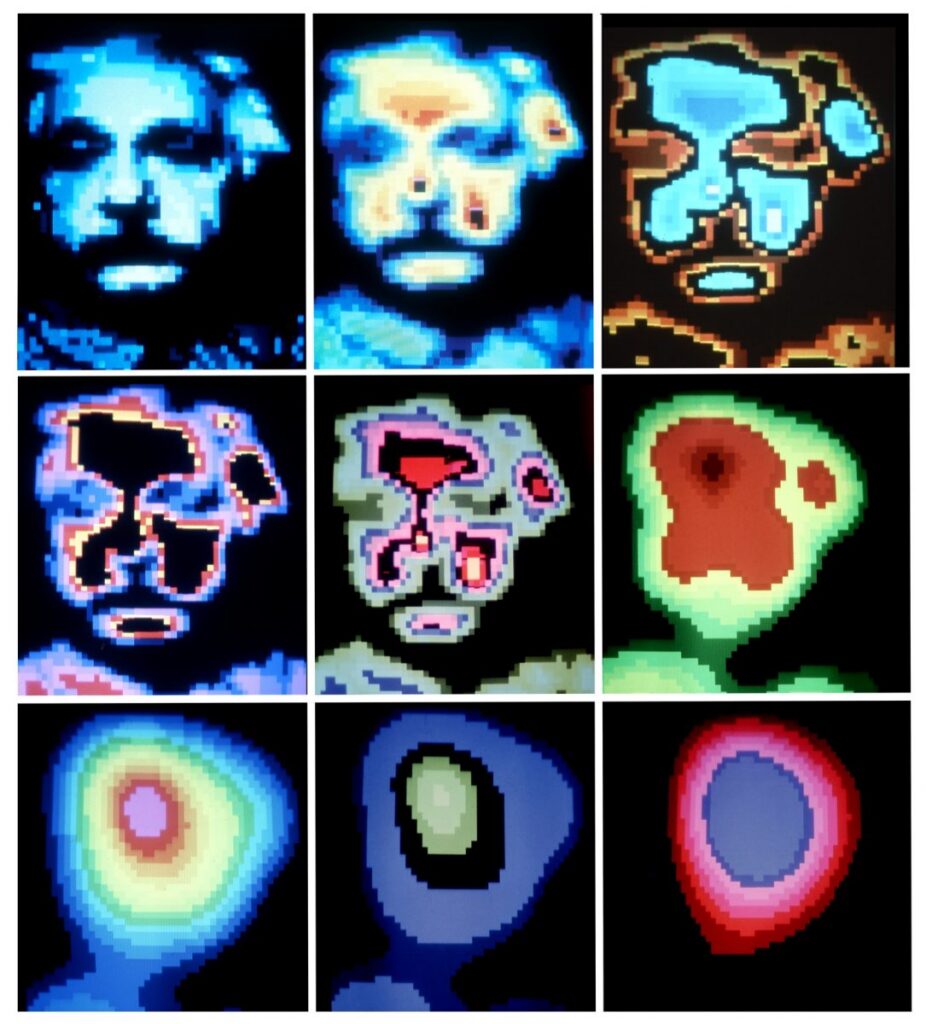

At this moment, however, the research that New Tendencies put on display shifted towards emerging digital technologies. Artist-engineers and teams of artists and engineers began producing works like Marc Adrian’s automatically generated letrasets, Georg Nees’ computer-generated drawings, and Herbert W. Franke’s computer-transformed scans of Albert Einstein’s portrait. The computer promised to create works that were functional instead of purely decorative, that could be mass produced and easily distributed. Whether or not these experiments in digital art were successful in terms of their constructivist goals was an open question at the time.

Umberto Eco, who had been involved in New Tendencies for some time, spoke at a symposium called “Computers and Visual Research,” saying that when he asks “what is the relationship of your art and your research with the needs of the masses at large?” the addressee is “often unsure about how to respond.”

He went on to say that an artist has two paths towards creating art that responds to the concerns of everyday people: the avant-garde and the mass media (in which he included the products of both Hollywood and Socialist Realism.4 This leads to a difficulty for avant-garde artists, insofar as they are bound to create art with revolutionary characteristics (either in terms of politics or aesthetics) but must compete to distribute it through channels that are almost necessarily conservative. The computer represented a chance to distribute art outside of the channels of elite galleries, tax-paying cinemas, and the pages of mainstream newspapers and magazines. But, when New Tendencies existed, computers were not yet accessible to the masses.

Perhaps surprisingly, Eco’s point of criticism has become sharper in the media landscape of the internet age. Although we all have access to computers and smartphones, the distribution of art flows through the (essentially conservative) algorithms of social media and Google search. These are platforms that, when push comes to shove, will not countenance the appearance of any art that has genuine revolutionary potential. Even worse and much like the art market of Mavignier and Meštrović’s time, these platforms are likely to transform any art that might have any such potential into simple commodities to be bought, sold, and owned.

I would love to one day see digital art that I would call Constructivist, that I felt showed a new tendency.

- Exhibition catalogue of tendencije 4, 1970, in A Little-Known Story About a Movement, a Magazine, and the Computer’s Arrival in Art, Eds. Margit Rosen, with Peter Weibel, Darko Fritz, and Marija Gattin, p. 344. [↩]

- Text in exhibition catalogue of nove tendencije 2, 1963, see p. 115 of NT & BI, Ed. Rosen. [↩]

- Rosen, Margit. “The Art of Programming: The New Tendencies and the Arrival of the Computer as a Means of Artistic Research” (2011), see p. 28 of NT & BI, Ed. Rosen. [↩]

- Untitled lecture at the Symposium “Kompjuteri i vizuelna istrazivanja [Computers and Visual Research]” (1969), see p. 415-18 of NT & BI, Ed. Rosen. [↩]