A review of False Clouds, a group exhibition at the National Museum of Bosnia & Herzegovina

False Clouds made a concise argument about the ways that pollution can hide in plain sight, setting off from the unfortunate irony that many scenes of seeming natural beauty are, in actuality, only as stunning as they are because of pollution. Sunsets would be less brilliant if smoke and smog didn’t intensify their colors. Clean lakes and rivers aren’t an Instagrammable shade of neon blue; that’s industrial run-off.

Armin Ćosić’s (b. 1997.) work, “Waterfall,” most neatly summed up the group exhibition’s central contention. Its shimmering mail of blue and green scales, lit from above and below, hung at the entry to the first of False Cloud’s exhibition rooms. Looking like the scales of a massive Orada, or perhaps something Gwenyth Paltrow would wear to the Met, it beautifies the dirty water bottles that Ćosić picked up off the street to create it.

Crucially however, this transformation doesn’t change the material, the plastic; thrown into a river, Ćosić’s art would act just the same as the bottles from which it was made. By showing us how easily the same material can look more or less beautiful in different presentations (formally: by exposing the limits of our aesthetic senses to accurately track ‘the natural’), the work demonstrates the delusory power of pollution that conceals itself.

Some works, like the large Triptych painting by Marianne Vlaschits, which zooms in to show us the physical characteristics of fine particulate matter, were more straightforwardly representational. By attempting to uncover what’s hidden from view, the art plays a revelatory function. The same goes for Melih Sarig’s watercolor of Sarajevo as seen from the winter mountains, called “Above the Sea of Smoke.”

Even if few can name the many different types of pollutants or trace their route into streams and airways, we all know about the impact of pollution on some level. We see how we live, what we buy and what we throw away. We’ve all seen what Sarajevo looks like from above during the wintertime.

That’s why I wonder whether “raising awareness” counts for very much. Ultimately, the way toward any cleaner world isn’t impeded by any question of knowledge. It’s about people acting on the knowledge they have, both in their personal lives and in their political choices. Of course it’s unfair to expect art to materially affect a crisis whose slight mitigation would require wholesale changes to the entire world’s political economy. But what then, in the context of environmental pollution as an emergency, is the proper role of an exhibition like False Clouds?

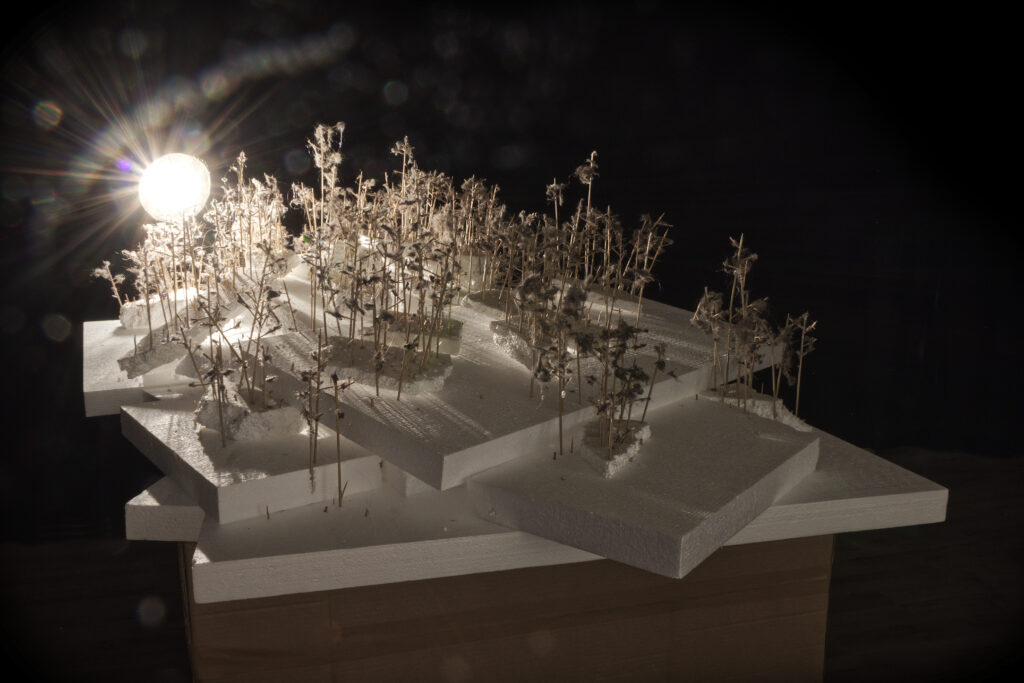

The answer I’m inclined to give emerges from the work (“Dendriod Reverie No. 2,” by Mattias Böhler and Christian Orendt) I’ve thought about the most since I saw the exhibition. There was a log, say 150cm long and cut from a fairly-sized tree, at whose end was a tablet playing a video of a multi-colored face, distorted and undulating. Over speakers played a voice of lament, heavily modulated and equally distorted—-recalling Radiohead. Only after a moment of puzzling over the odd work do you realize the log lies on an ambulance stretcher. It seems terminal for the tree, the lament dying but not without a final reserve of hope.

And what’s the answer? Environmental art must express honesty beyond the factual and hope before the fantastical. After that it’s up to us.

Photography courtesy of the curator Gabriela Manda Seith.